The Arabs

For centuries before: The Arab Lakhmid had been Sassanian Persian vassals and the Arab Ghassanids were vassals of the Byzantine Empire. They acted as frontier guardians of the two empires against fellow Arabs: While the Meccan and Medinese Arabs of Arabia had established commercial connections with both the Byzantines and Sassanids Empires.

The Lakhmids

The Lakhmids were a group of Arab Christians who lived in Southern Iraq, and made al-Hirah their capital in (266). The al-Hirah ruins are located 3 kilometers south of Kufa, on the west bank of the Euphrates. The Lakhmid Kingdom was founded by the Lakhum tribe that immigrated out of Yemen in the second century and ruled by the Banu Lakhm, hence the name given it. The founder of the dynasty was 'Amr, whose son Imru' al-Qais converted to Christianity. Gradually the whole city converted to that faith. Imru' al-Qais dreamt of a unified and independent Arab kingdom and, following that dream, he seized many cities in Arabia . He then formed a large army and developed the Kingdom as a naval power, which consisted of a fleet of ships operating along the Bahraini coast. From this position he attacked the coastal cities of Persia (Iran) (which at that time was in civil war, due to a dispute as to the succession), even raiding the birthplace of the Sassanid kings, the province of Pars (Fars). |

In 325, the Persians, led by Shapur II, began a campaign against the Arab kingdoms. When Imru' al-Qais realized that a mighty Persian army composed of 60,000 warriors was approaching his kingdom, he asked for the assistance of the Roman Empire. Constantius II promised to assist him but was unable to provide that help when it was needed. The Persians advanced toward al-Hirah and a series of vicious battles took place over al-Hirah and the surrounding cities. Shapur II crushed the Lakhmid army and captured al-Hirah. He ordered the extermination of its population in retaliation of their raids on Pars. In this, the young Shapur acted much more violently than was normal at the time in order to demonstrate to both the Arab Kingdoms and the Persian nobility his power and authority.

The Ghassanids

The Ghassanids were a group of South Arabian Christian tribes that emigrated in the early 3rd century from Yemen to Hauran in southern Syria, Jordan and the Holy Land where they intermarried with Hellenized Roman settlers and Greek-speaking Early Christian communities. Modern Syrians are a mix of these three peoples. |

|

Seeing the success of these raids, caliph Abu Bakr decided upon a full-scale invasion of Iraq; by November of that year, Iraq was taken. An Arab victory at Al-Qadisiyyah Iraq in 637 A.D. lead directly to the sack of the Sassanian winter capital at Ctesiphon on the Tigris. After withdrawal from Ctesiphon, the Persian armies gathered at Jalaula, north-east of Ctesiphon. There they were defeated by Arab forces under the command of Hashim ibn Uthba. After the defeat of Persian forces at the Battle of Jalula, Emperor Yazdgerd III went to Rayy, and from there he moved to Merv, where he set up his capital. From Merv, he directed his chiefs to conduct continuous raids in Iraq to destabilize the Muslim rule in Iraq. Within the next four years, Yazdgerd III felt powerful enough to challenge the Muslims once again for the throne of Iraq. The Emperor sent a call to his people to drive away the Muslims from their lands. In response to the call, hardened veterans and young volunteers from all parts of Persia marched in large numbers to join the imperial standard and marched to Nihawand for the last titanic struggle for Persia. Again they were defeated, after the devastating defeat at Nihawand, Yazdgerd III was never again able to raise significant troops to resist the mighty onslaught of the Arabs. Yazdegerd III fled into Media, where his generals tried to organize a new resistance.

Sometime during the wars, caliph Omar Ibn-Khattab is reported to have written this letter to Yazdgerd IIIText of the ultimatum from Omar Ibn-Khattab the Calif of Islam to the Yazdgerd IIIBism-ellah Ar'rahman Ar'rhim To the Shah of the Fars I do not foresee a good future for you and your nation save your acceptance of my terms and your submission to me. There was a time when your country ruled half the world, but see how now your sun has set. On all fronts your armies have been defeated and your nation is condemned to extinction. I point out to you the path whereby you might escape this fate. Namely, that you begin worshipping the one god, the unique deity, the only god who created all that is. I bring you his message. Order your nation to cease the false worship of fire and to join us, that they may join the truth. Worship Allah the creator of the world. Worship Allah and accept Islam as the path of salvation. End now your polytheistic ways and become Muslims that you may accept Allah-u-Akbar as your savior. This is the only way of securing your own survival and the peace of your Persians. You will do this if you know what is good for you and for your Persians. Submission is your only option Allah u Akbar The Calif of Muslims Omar Ibn-Khat'tab The response:In the name of Ahuramazda the Creator of Life and WisdomFrom the Shahan-Shah of Persia Yazdgerd to Omar Ibn Khat'tab the Arab Calif. In your letter you summon us Persians to your god whom you call "Allah-u-Akbar"; and because of your barbarity and ignorance, without knowing who we are and Whom we worship, you demand that we seek out your god and become worshippers of "Allah-u-Akbar". How strange that you occupy the seat of the Arab Calif but are as ignorant as any desert roaming Arab! You admonish me to become monotheistic in faith. Ignorant man, for thousands of years we Aryaee have, in this land of culture and art, been monotheistic and five times a day have we offered prayers to God's Throne of Oneness. While we laid the foundations of philanthropy and righteousness and kindness in this world and held high the ensign of "Good Thoughts, Good Words and Good Deeds", you and your ancestors were desert wanderers who ate snakes and lizards and buried your innocent daughters alive. You Arabs who have no regard for God's creatures, who mercilessly put people to the sword, who mistreat your women and bury you daughters alive, who attack caravans and are highway robbers, who commit murder, who kidnap women and spouses; how dare you presume to teach us, who are above these evils, to worship God? You tell me to cease the worship of fire and to worship God instead! To us Persians the light of Fire is reminiscent of the Light of God. The radiance and the sun-like warmth of fire exuberates our hearts, and the pleasant warmth of it brings our hearts and spirits closer together, that we may be philanthropic, kind and considerate, that gentleness and forgiveness may become our way of life, and that thereby the Light of God may keep shining in our hearts. Our God is the Great Ahuramazda. Strange is this that you too have now decided to give Him a name, and you call Him by the name of "Allah-u-Akbar". But we are nothing like you. We, in the name of Ahuramazda, practice compassion and love and goodness and righteousness and forgiveness, and care for the dispossessed and the unfortunate; But you, in the name of your "Allah-u-Akbar" commit murder, create misery and subject others to suffering! Tell me truly who is to blame for your misdeeds? Your god who orders genocide, plunder and destruction, or you who do these things in his name? Or both? You, who have spent all your days in brutality and barbarity, have now come out of your desolate deserts resolved to teach, by the blade and by conquest, the worship of God to a people who have for thousands of years been civilized and have relied on culture and knowledge and art as mighty supports. What have you, in the name of your "Allah-u-Akbar", taught these armies of Islam besides destruction and pillage and murder that you now presume to summon others to your god? Today, my people's fortunes have changed. Their armies, who were subjects of Ahuramazada, have now been defeated by the Arab armies of "Allah-u-Akbar". And they are being forced, at the point of the sword, to convert to the god by the name of "Allah-u-Akbar". And are forced to offer him prayers five times a day but now in Arabic; since your "Allah-u-Akbar" only understands Arabic. I advise you to return to your lizard infested deserts. Do not let loose upon our cities your cruel barbarous Arabs who are like rabid animals. Refrain from the murder of my people. Refrain from pillaging my people. Refrain from kidnapping our daughters in the name of your "Allah-u-Akbar". Refrain from these crimes and evils. We Aryaee are a forgiving people, a kind and well-meaning people. Wherever we go, we sow the seeds of goodness, amity and righteousness. And this is why we have the capacity to overlook the crimes and the misdeeds of your Arabs. Stay in your desert with your "Allah-u-Akbar", and do not approach our cities; for horrid is your belief and brutish is your conduct. Yazdgerd Saasaani |

But the Battle of Nahavand (642 A.D.), south of Hamadan, put an end to their hopes. Yazdegerd III spent the rest of his life as a fugitive, eluding capture and fermenting rebellion wherever he could. It is said that he spent time in China before winding up in the empire's northeastern outpost of Merv, whose Marzban, or March-lord named Mahuyeh, soon became soured by the imperious and expensive demands of Yazdegerd III. Mahuyeh turned against his Emperor and defeated him with the help of Hephthalites from Badghis. {The Hephthalites were a powerful nomadic confederation of White Huns from Central Asian. The Hephthalites had troubled the Sassanids since at least 590 A.D, when they had sided with Bahram Chubin, Khosrow Parviz's rebel general}. A Miller near Merv murdered the fugitive Emperor Yazdegerd III for his purse at Merv in 651 - under the instruction of Mahuyeh it is said. Yazdegerd III's daughter Shahr Banu, would marry the grandson of Muhammad, Husayn ibn Ali, and gave birth to the fourth Shia Imam, Ali Zayn al Abidin.

There are no available chronicles of the Human events which occurred during the battle for Persia. This short play "Parvin the Daughter of Sassan" seems to capture the "feel" of those times.Parvin the Daughter of Sassan by Hedayat, Sadeq (First printing 1934, Tehran) Sadeq Hedayat was an Iranian nationalist living in self-imposed exile in Paris during the first part of the 20th century, he came from an aristocratic Qajar (Turkic) family background. (See below). Play Setting Location Setting: A house in the ancient city of Rey (close to present day Tehran) bearing a late Sassanian style of architecture. Period of time: After the defeat of the Sassanian federal armies at Qadissya, and Nahavand. Various cities in Persia are left to defend for themselves. With the western part of the country already overrun by the invaders, and the heartland of Persia coming under attack, the specter of the Arab army assault on the city lurks in the air. Actors Actor: 1. Bahram: A 50 year old house servant Actor 2: Chahreh Pardar (Sassan): 45 year old father of the house Actor 3: Parvin: 20 year old, tall, and beautiful daughter of Chahreh Pardar Actor 4: Parviz: 25 year old handsome fiance of Parvin, bearing his military gear Actors 5-9: Four men dressed in Arab military costumes, speaking Arabic Actor 10: The leader of the Arabs, a barefoot, middle aged man wearing a sword and a dagger carrying on with a loud voice. Actor 11: Translator, a 40 year old man speaking in a thick accent Not shown but heard and mentioned: The loyal family dog, guarding the house The Play Hedayat’s brilliance as an able and creative writer and his sense of nationalism come together to create an emotionally charged play on the life of an upper class household in the ancient city of Rey in its last remaining days under the nominal rule of the Sassanians. The Arab forces that have taken city after city in Western Persia are now within the reach of Rey, and are expected any day. The city lies open, and has no natural defenses. A local defense force comprising of mostly young men remaining in the city has been assembled and provides round the clock vigilance against the hostile troops that might appear anytime. The sad knowledge that their small defensive force will easily be out-numbered by many orders of magnitude is heavy on everyone’s mind, although not mentioned as if in self denial. Their hope is that their home terrain advantage will help them. The citizens remain hopeful that help in the form of military assistance will come from other cities to the North and the East so they can put up a consolidated defense against the invaders. In a self reassuring manner, there is also the belief that their divine land is protected by Ahura-Mazda against the impending genocide that has already consumed the Western half of the country. The horror stories of wholesale killing, plunder, looting, and rape, and reports of female citizens being sent off to Arabia to be sold in slave auctions, have been pouring into the city by the few lucky escapees from the other settlements to the West that were laid to waste at the hand of the aggressors. There is a sense of gloom in the air. The three part play starts with Bahram, the household servant, attending to the large sized courtyard of the house, and reflecting loudly on the general state of affairs. He cannot apprehend the logic of his employee who seems incapable of comprehending the full weight of what is about to unfold. He wonders why Chahreh Padar, who has the means, has not left in the direction of China and Turan as have so many others of his standing. Deep inside, he has a feeling this house will be one of the first targets of assault by the plundering aggressors and is trying to figure his odds of defending the house with the help of the faithful family dog (a symbol of faithfulness and animal affection in ancient Persia) once house to house assaults in the city get underway. The news pouring into the city is not encouraging at all. The supplies are running scarce, as a breakdown of commerce seems to have occurred. Bahram’s thought process is broken by his employer, Chahreh Padar (Sassan) appearing on the scene and asking if Bahram is talking to himself. He then asks Bahram to go to the outskirts of the city looking for his future son-in-law Parviz who has joined the city defense forces. Parviz has not stopped by in quite a few days, and Chahreh Padar knows his daughter Parvin is longing to see his fiancé. Bahram expresses his reservation about the wisdom of staying on in Rey and says that there may still be time to get out. Chahreh Padar wants to hear none of that, given his childhood experience of being uprooted from the southwestern region of the country due to incursion by the Arab tribes and having moved to Rey in search of safety. Almost in a state of denial of the impending disaster that is to befell the city and its citizens, Chahreh Padar seems to have convinced himself that no harm will come. As Bahram departs, Chahreh Padar’s beautiful daughter Parvin appears in the courtyard of the house and is asked by her father to play a musical instrument as a means of combating the gloom and doom.

Soon Parviz arrives, to the joy of his fiance and her father, unaware of Bahram having been dispatched to get him. The exchange of news and views center about the defensive activities around the city. Parviz feels it is his honor and duty to defend the motherland, and that divine protection will be with them as they face incredible odds. Chahreh Padar is very supportive, and shows Parviz a small drawing of his daughter. Parviz asks if he can have the drawing and take it with him. Chahreh Pardar states that the drawing is something he is saving for his old age, but as long as his daughter is still living with him, Parviz can take the drawing with him, and hands it over. He goes on to say once this temporary problem is over with, the wedding of Parviz to his daughter will take place. As Parviz is getting to depart his fiance, she hands him the wedding ring she has been saving for their wedding day, and he gives her the gold ring he has procured for the same occasion. The departure scene is emotionally moving, as Parviz mounts his white horse to return to his observation post outside the city. Then comes the assault on the city, and with the residents of the house very much confined within the enclosure of the house. Bahram enters Chahreh Padar’s room and sees Parvin sitting by her father’s bed side. Bahram finds a way to tell them that their house seems to have been penetrated by the invaders. He reports that the night before, he saw the glitter of one of the intruders’ eyes peeking from behind a tree in the courtyard and looking in the direction of their rooms, lit by candle light. Apparently Bahram, and the family dog were successful in scaring the Arab off. However, Bahram was sure they will return tonight. Chahreh Pardar starts to hallucinate. Parvin insists she will stay by father’s bedside to care for him. Suddenly, they hear footsteps of people walking on the roof. Anxiety builds. Bahram is wondering whether the family dog can scare the intruders away. Soon afterwards there is the sound of people walking outside. Bahram rushes to lock the door. There is banging on the door of the room. Chahreh Pardar tells Bahram, they are breaking down the door, and that he should open it. Bahram is thrown aside by four cruel looking intruders who enter the room. Speaking in Arabic, and not being understood by the three Persians, the intruders soon inflict a fatal blow to Bahram who positions himself between the invaders and the his employer. It is clear the faithful family dog was also killed by the looters. The intruders start to gather all the valuables in the room. Finally they look in the direction of Parvin. Realizing their ill intention towards his daughter, Chahreh Pardar while still in bed cries out that they can take all his material belongings but must leave his daughter alone. He then tries to shelter his daughter as the four Arabs close in. His attempt to save his daughter is met with a fatal blow. Parvin, witnessing all of these terrible events, loses consciousness. The final and the climactic episode of the play takes place at the location in the city where the leader of the Arab invasion force is found. This episode brings out the stark contrasts between what was and what is to be. Parvin, wrapped in a blanket, is brought into the room where the Arab leader is pacing up and down. The four assailants, having looted Chahreh Padar’s house, and having stashed away their ill gotten goods, unwrap the blanket at the foot of their leader. Parvin, still fainting, comes into view. They all stare at her. Soon afterwards, she starts to come around, and as she gains consciousness, the sight of the strangers bent over to look at her shocks her. Suddenly, the memory of the murder scene comes back to her. The Arab leader throws the others out of the room, and makes gestures towards Parvin. She shrinks back in disgust. The leader, frustrated, rushes to the door, and shouts some words in Arabic. A second man comes in, and walks towards Parvin. The leader leaves them alone and walks to the other end of the room. The new arrival starts to speak in Pahlavi (the language spoken in Persia in those days) with an accent. Parvin is trying to find out whether this man is an outsider who has learnt Pahlavi or an Persian traitor. The translator and Parvin engage in very revealing and charged exchanges that clearly highlight the drastic changes that are about to befall the society. He informs Parvin that the Arab leader has a generous offer reserved for her. She is to become the latest addition to his harem and all other women in the Harem will be required to serve her. She is told how lucky she is to receive this offer, given that the other women in the city are to be sent to Arabia to be sold at slave auctions. She is to be spared, and kept by the leader. All this talk is alien to Parvin who shows her disdain. She expresses her disgust at the conduct of the aggressors, and in response to the translator points out that ancient Persians, in the course of their history, have only fought defensive wars, and have never attacked their neighbors for the purpose of looting or imposing their religion on them. The translator insists Parvin must accept the new realities, that the Fire Temples are things of the past to be abolished, and that she should submit to the will of Allah, and learn the new language as Pahlavi will also soon be abolished. Parvin feels the defense of her country is on her shoulders and expresses her thoughts that finally good will prevail and these invaders’ days are numbered. She believes strongly that her fiance Parviz will come to save her. The translator, who seems to be pressured to get Parvin to comply, suddenly shows her a ring. Parvin, recognizing the ring as the one she had given to Parviz, is panic-stricken and asks where the ring came from. The translator, feeling he is getting an advantage, discloses that when the Arab army arrived, the defenders fought gallantly but were no match for the invading forces. After all the defenders were felled, he and a few others were trusted by the leader to enter the field and remove all valuables from the dead Persians, interrogating and finishing off any who were still breathing. He goes on to say that while doing so that night, he saw a white stallion on a hilltop bent over his dying master. He went over to investigate. Thinking he was an Persian speaking his language, the dying soldier, covered in his own blood, motioned the newcomer to approach him. The soldier gave him the drawing of a girl and a ring and asked him to find this girl and to tell her not to wait for him. The figure of the girl depicted in the drawing caught the eye of the Arab leader, who asked for the girl to be found and brought to him for addition to his own harem. Hearing all of this, Parvin’s world suddenly comes crumbling down around her. Her last hopes are dashed. At this point the translator reiterates the offer made to Parvin before, hoping she is more amenable by then. Parvin is still defiant, and rejects the offer with the force of her conviction. The translator points out this is the last chance she is getting, and still hearing “no,” walks to the other side of the room. The Arab leader, impatient and pacing up and down the room, stops to hear the translator’s report. With rage in his face, he tosses the translator out of the room and walks towards Parvin. There is silence as the Arab approaches Parvin. He mutters some words and then puts one arm around Parvin, and places his other hand under her chin as if appraising his prey, and then kisses Parvin. In that closeness Parvin reaches out and gently pulls out the dagger tied to the Arab leader’s belt. Unaware of Parvin’s action, the Arab leader, pleased at his initial success, pulls back. As he looks the other way, Parvin raises the dagger. With all the strength that she can muster and with great swiftness the dagger comes down piercing through her chest. As her blood gushes out, Parvin falls to the ground to join the rest of her family. The Arab leader, shaken by the event, walks away, reaches inside of a big chest filled to the top with jewels stolen from the Persian people, and pulls out a handful to cover the body of his latest victim. |

| Sassanian King ListArdashir I from 224 to 241. Shapur I from 241 to 272 Hormizd I from 272 to 273. Bahram I from 273 to 276. Bahram II from 276 to 293. Bahram III year 293. Narseh from 293 to 302. Hormizd II from 302 to 310. Shapur II from 310 to 379 Ardashir II from 379 to 383. Shapur III from 383 to 388. Bahram IV from 388 to 399. Yazdegerd I from 399 to 420. Bahram V from 420 to 438. Yazdegerd II from 438 to 457. Hormizd III from 457 to 459. Peroz I from 457 to 484. Balash from 484 to 488. Kavadh I from 488 to 531. Djamasp from 496 to 498. Khosrau I from 531 to 579. Hormizd IV from 579 to 590. Khosrau II from 590 to 628. Bahram VI from 590 to 591. Bistam from 591 to 592. Hormizd V year 593. Kavadh II year 628. Ardashir III from 628 to 630. Peroz II year 629. Shahrbaraz year 630. Boran and others from 630 to 631. Hormizd VI (or V) from 631 to 632. Yazdegerd III from 632 to 651 |

ARABIA

Topography

The Arabian Peninsula, is a quadrilateral land mass. It covers an area of about 2,250,000 sq. km. The vast landscape is composed of a variety of habitats such as mountains, Valleys (Wadis), sandy and rocky deserts, meadows (Raudhahs), salt pans (Sabkhahs) and lava areas (Harrats), etc. In a broad geographical sense, Saudi Arabia can be divided into two distinct zones; the narrow strip of rain fed highlands of the western and southwestern regions close to Africa. These mountains on the western side, especially the Asir Mountains are characterized by cool climate, high precipitation and high humidity. The landscape of the region holds a variety of plants, most of which have an affinity with the plants of nearby East African countries. The spectacular beauty and pleasant climate of the Asir Mountains attract many people from the central and eastern parts of the country during summer. The mountains of Jizan Region, especially the Fayfa Mountains reach a height of about 2000 m. The west facing slopes are steep while its eastern side slopes gently towards the inland plateau.

And the vast arid and extra arid lands of the interior (Najd). The Najd area, which occupies the lions share of Arabia, is located on the eastern side of the entire Sarawat Mountains and adjoining areas. It has a varied and deserted- topography such as vast sand seas, bare plateaus, small mountains, plains, etc. The deserts are composed of Aeolian sands and are more or less continuous with Great Nafud in the north and Rub al-Khali in the south, both of which are connected by an arch shaped Dahna sands. The Central Region in general, is characterized by patchy, gravel deserts, hillocks and wadis whereas northern and north-central regions of the country are an exposed complex of Pre Cambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks.

History

Historically, Arabia came be divided into three parts: the relatively advanced African Western part, the Northern Middle Eastern part, and the little known Eastern part (in the historical sense).

Historically, Arabia came be divided into three parts: the relatively advanced African Western part, the Northern Middle Eastern part, and the little known Eastern part (in the historical sense).Hebrew-Roman historian Josephus describes a place called Saba, as a walled royal city of Ethiopia, which Persian king Cambyses afterwards named Meroe. He says "it was both encompassed by the Nile quite round, and the other rivers, Astapus and Astaboras" offering protection from both foreign armies and river floods. According to Josephus it was the conquering of Saba that brought great fame to a young Egyptian Prince, simultaneously exposing his personal background as a slave child named Moses.

Modern archaeological evidence increasingly supports Sheba being located in modern Yemen at or near the site of the famous Marib Dam, which was first built more than 2500 years ago. Some scholars suggest a link to the Sabaeans of southern Arabia. A number of sources claim that the people of Sheba controlled trade in the Red Sea, and expanded at some point from Arabia into Africa to found trading posts in the lands currently called Eritrea and Somalia.

In the medieval Ethiopian cultural work called the Kebra Nagast, Sheba was located in Ethiopia. Some scholars therefore point to a region in northern Tigray and Eritrea which was once called Saba (later called Meroe), as a possible link with the Biblical Sheba. Other scholars link Sheba with Shewa (also written as Shoa, modern Addis Ababa) in Ethiopia. Ruins in many other countries, including Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, Egypt, Eritrea and Iran have been credited as being Sheba, but with only minimal evidence. There has even been a suggestion of a link between the name "Sheba" and that of Zanzibar (“San-Sheba”).

| Sun temple - The Bar'an temple in Ma'rib. Known as Bilqis Throne (the Arabic name for the Queen of Sheba), it was built in the 8th century B.C. dedicated to Wadd (Ilumquh) and performed its function for nearly 1000 years. |

|

One of the earliest recorded instances of Arabs at war, is found in an Assyrian account of a war fought with Arabs between 853 and 626 B.C.

|  |

The Himyarites followed the Sabaeans as the leaders in southern Arabia; the Himyarite Kingdom lasted from around 115 B.C. to around 525 A.D. In 24 B.C. the Roman emperor Augustus sent the prefect of Egypt, Aelius Gallus, against the Himyarites, but his army of 10,000 was unsuccessful and returned to Egypt. The Himyarites prospered in the frankincense, myrrh, and spice trade until the Romans began to open the sea routes through the Red Sea. During the Roman period the peninsula was divided by three districts: Arabia Felix, Arabia Deserta, and Arabia Petraea. The latter included the Sinai Peninsula, which is no longer considered part of the modern Arabian Peninsula.

In the 3rd century A.D, The East African Christian Kingdom of Aksum began interfering in South Arabian affairs, controlling at times the western Tihama region among other areas. The Kingdom of Aksum at its height extended its territory in Arabia across most of Yemen and southern and western Saudi Arabia, before being eventually driven out by the Persians. There is evidence of a Sabaean inscription about the alliance between the Himyarite king Shamir Yuhahmid and the Aksum King in the first quarter of the 3rd century A.D. They had been living alongside the Sabaeans, who lived across the Red Sea from them for many centuries.The ruins of Siraf, a legendary ancient port, are located on the north shore of the Iranian coast on the Persian Gulf. The Persian Gulf was a boat route between the Arabian Peninsula and India, made feasible for small boats by staying close to the coast with land always in sight. The historical importance of Siraf to ancient trade is only now being realised. Discovered there in past archaeological excavations are ivory objects from east Africa, pieces of stone from India, and lapis from Afghanistan. Sirif dates back to the Parthian era. There is a lost city in The Empty Quarter, known as Iram of the Pillars and Thamud. It is estimated that it lasted from around 3,000 B.C. to the first century A.D.

Arab Rule in Persia

With the fall of the empire, the fate of its religion was also sealed. Though the Muslims officially tolerated the Zoroastrian faith, desecrations, humiliations, and other such provocations were common; and persecutions were not unknown. The Muslims also used government policy to encourage conversion to Islam: The first edict was that only a Muslim could own Muslim slaves or indentured servants. Thus, a bonded individual owned by a Zoroastrian, could automatically become a freeman by converting to Islam. The other edict was that if one male member of a Zoroastrian family converted to Islam, he instantly inherited all its property.

Today, there are but a handful of Zoroastrians in Iran. It is said that some Zoroastrians immigrated to western India, where they are now chiefly concentrated in Mumbai (Bombay). There they are known as Parsi, {descriptions of these people in the 1831 book "The Modern Traveler" by Josiah Condor, suggests that they are Persian in religion only}. They have preserved only a relatively small portion of the sacred writings, but they still number their years by the era of Yazdegerd III, the last king of their faith, and the last Sassanian sovereign of Persia.

As an interesting confirmation that Whites behave exactly the same, regardless of religion. The ancient symbol of Zoroastrianism was the Faravahar: A Bearded Black Man, with one hand pointing outward and up, while the other holds a ring (below). As was done with the Hebrew faiths, Whites have turned a Black religion into theirs, complete with a "New" symbol; which is now the standard Whitenized "Jesus-like" image (below).

|  |

From the first, pagans and idolaters (mostly Arab tribes at the beginning) were given the choice of conversion to Islam or death. This is the Islamic concept of jihad or holy war. However, beginning with the Jews at Yathrib and elsewhere in Arabia, and traditionally with the Christians of Najran. Muhammad recognized their having been blessed by Allah in possessing earlier revelations in the form of their scriptures. So while they were invited to submit to his new revelation, they were not required to do so; but if they did not, they would be taxed as subjects of their former country. Later defeated non-Arab peoples outside of Arabia who were Christians, Jews or Zoroastrians, were required to pay both a head tax, and an annual property tax, but likewise, were not required to abandon their faiths, or convert to Islam. However, when non-Arabs converted to Islam, they were exempted from the head tax, a substantial incentive to convert.

The Prophet Muhammad, had made Medina his capital, and it was there that he died. Leadership then fell to Abu Bakr (632-634), Muhammad's father-in-law and the first of the four orthodox Caliphs, or temporal leaders of the Muslims. Umar followed him (634-644) and organized the governmental administration of captured provinces. The third caliph was Uthman (644-656), under whose administration the compilation of the Quran is said to have been accomplished. The Umayyad dynasty

The Umayyad dynasty

Upon the murder of Uthman, an aspirant to the caliphate was Ali, Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law. Ali became caliph in 656. The Arab governor of Damascus, one Muawiya who had been the heir-apparent to the pagan throne of Mecca, which was occupied by his father Abu Sufyan and mother Hind. After the defeat of his family following the taking of Mecca by Muhammad, Muawiya converted to Islam. Muhammad welcomed his former opponents, enrolled them in his army and gave them important posts in what was to become the Caliphate.Muawiya, refused to recognize Ali, and in 656 he mounted his own claims to the Caliphate. When Ali agreed to negotiate with Muawiya, Ali's own followers were divided and began to fight among themselves. Ali sided with one group, the Shiites; and defeated the other group, the Sunnis in 658. Later, Ali moved his capital to Kufa Iraq, and was later assassinated at Kufah in 661. Ali's followers established the first of Islam's dissident sects, the Shia (from Shiat Ali "party of Ali"). Those before and after Ali's succession remained the orthodox of Islam; they are called Sunnis - from the word sunnia meaning orthodox.

After Ali's death, Muawiya was recognized as Caliph by all Muslims except the Shiites. The Umayyad dynasty, whose name derives from Umayya ibn Abd Shams, the great-grandfather of Muawiya. During the Ummayad period, 656-750, the Caliphs made Damascus their headquarters. This period in Islamic history is known as the Arab Kingdom and the Caliphs acted as an emperor over an empire that eventually by 750 extended from Pakistan, western India and the frontiers of China in central Asia to northwest Africa, Spain and southern France in the West.

Muawiya made a peace treaty with Emperor Constantine II that lasted from 659-661. After 661, Arab armies fought their way across what is now Turkey and took the city of Chalcedon, 30 miles east across the Bosporus from Constantinople. Every year from 673-677, the Muslim land and naval forces launched full-scale attacks on Constantinople without success. Meanwhile a second campaign against Carthage and northwest Africa was launched from 670-683. Muawiya again made a peace treaty with the Romans in 678 that lead to increasing commercial exchange and the employment of Roman technical assistance for the Muslims. Particularly, Roman craftsmen who were employed to supervise the building of the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem, and both the Umayyad palace and great mosque at Damascus.

Problems of the Conquest

Soon After their victory; factionalism was growing among Arabs, partly the result of the jealousies and rivalries that accompanied the acquisition of new territories and partly the result of the competition between the first arrivals in Persia, and those who followed.

In Persia the first Arab conquerors had concluded treaties with local Persian magnates who had assumed authority when the Sassanian imperial government disintegrated. These notables—the marzbans and landlords (dehqans)—undertook to continue tax collection on behalf of the new Muslim power. The advent of Arab colonizers, who preferred to cultivate the land rather than campaign farther into Asia, produced a further complication. Once the Arabs had settled in Persian lands, they, like the Persian cultivators, were required to pay the kharaj, or land tax, which was collected by Persian notables for the Muslims in a system similar to that which had predated the conquest. The system was ripe for abuse, and the Persian collectors extorted large sums, arousing the hostility of both Arabs and Persians. |

Another source of discontent was the jizyah, or head tax, which was applied to non-Muslims of the tolerated religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. After they had converted to Islam, Persians expected to be exempt from this tax. But the Umayyad government, burdened with imperial expenses, often refused to exempt the Persian converts. The tax demands of the Damascus government were as distasteful to those urbanized Arabs and Persians in commerce, as they were to those in agriculture, and hopes of easier conditions under the new rulers than under the Sassanids were not fully realized.

|  |

The Umayyads ignored Persian agricultural conditions, which required constant reinvestment to maintain irrigation works and to halt the encroachment of the desert. This no doubt made the tax burden, from which no returns were visible, all the more odious. Furthermore, the regime failed to maintain the peace so necessary to trade. Damascus feared the breaking away of remote provinces where the Arab colonists were becoming assimilated with the local populations. The government, therefore, deliberately encouraged tribal factionalism in order to prevent a united opposition against it.

While in Syria, Muawiyah cultivated the goodwill of Christian Syrians by recruiting them for his army at double pay, appointing Christians to many high offices, and by appointing his son by his Greek Christian wife as his successor. (Since the time of Alexander, the Greeks had built many cities in Syria, and had become the dominate element of the population. By virtue of the Roman occupation, most had become Christians. The province of Syria included the modern elements of Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria). The Syrian army became the basis of Umayyad strength, enabling the bypassing of Arab tribal rivalries. It was under a later Umayyad Caliph, Umar II (reigned 717-720), that discontented mawali (non-Arab Muslims) were placed on the same footing with all other Muslims, without respect to nationality. This decree allowed Greeks, Turks and other Eurasians to fully assimilate into the Muslim brotherhood. Problem was, these mawalis (clients) were often better educated and more civilised than their Arab masters. The new converts, now with the basis of equality of all Muslims, transformed the political landscape.

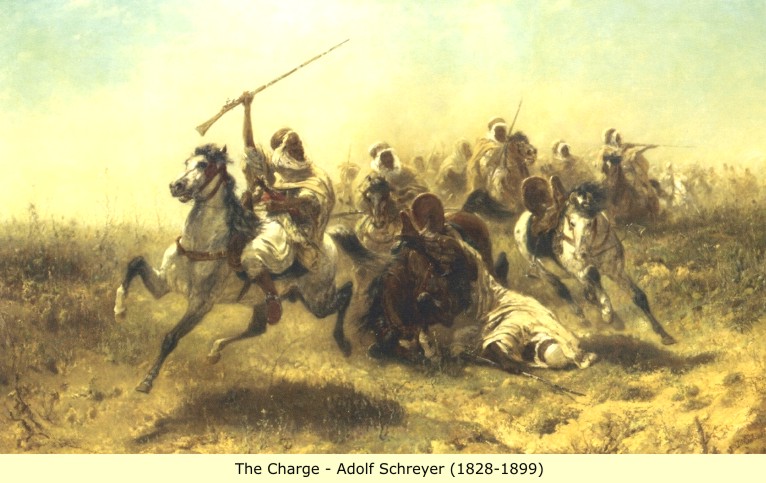

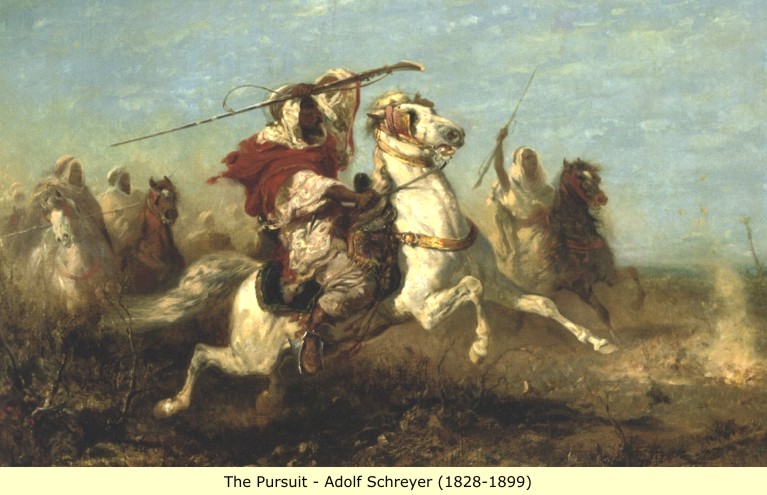

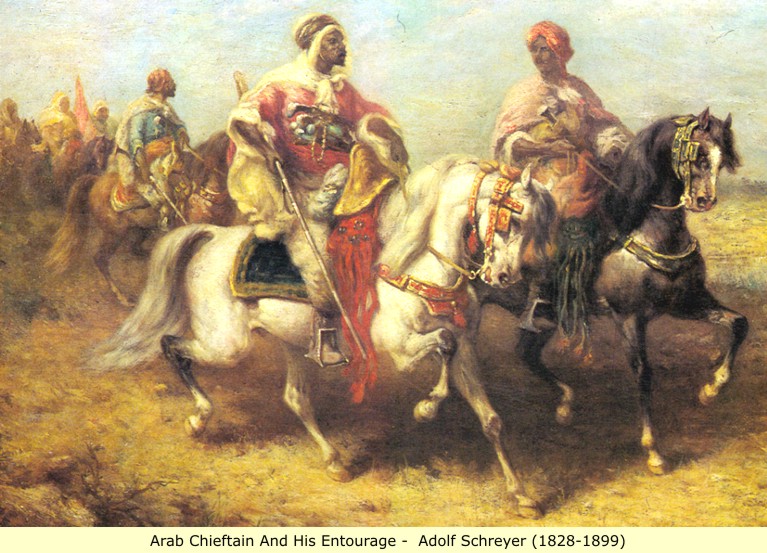

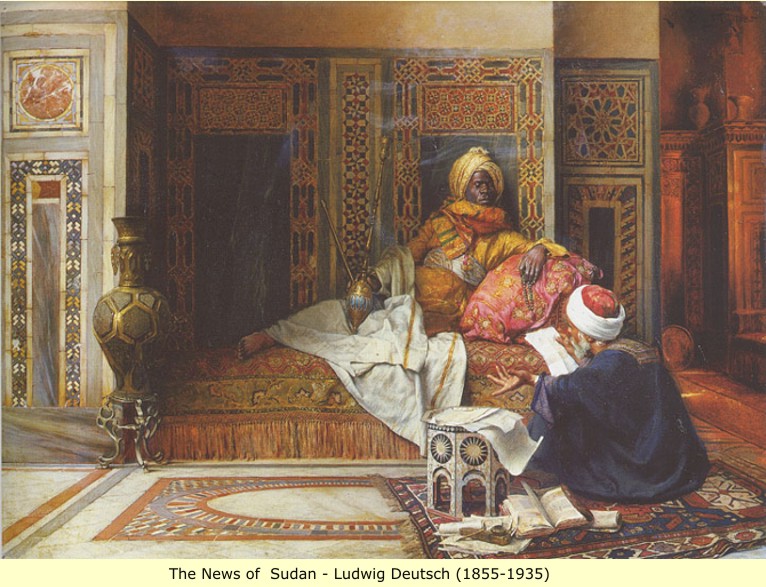

19th century paintings of Arabs

|  |

The Abbasid dynasty

Later the mawali became involved with the Hashimiyah, a religious/political sect that denied the legitimacy of Umayyad rule. The movement appeared in the Iraqi city of Kūfah in the early 700s among supporters of the fourth caliph Alī. They believed that succession to Alī’s position of imam, or leader, of the Muslim community had devolved to Muhammad ibn al-hanafīyah (d. 700), one of his sons, and Abū Hāshim, a grandson. The Hashimiyah thus did not recognize, for religious reasons, the legitimacy of Umayyad rule, and when Abū Hāshim died in 716 without heirs: the Hashimiyah, proclaimed as caliph Abu al-'Abbas as-Saffah. As-Saffah was the head of one branch of the Banu Hashim, which traced their lineage to Hashim, a great-grandfather of Muhammad, via al-Abbas, an uncle of the prophet. In 743, the death of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham provoked a civil war in the Islamic Empire. Abu al-Abbas as-Saffah , supported by Shi'as, Kharijis, and the residents of Khurasan, led his forces to victory over the Umayyads and ultimately deposed the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II in 750. As-Saffah thereby became first Caliph of the Abbasid dynasty. The Abbasid dynasty would rule over Islam for approximately the next 500 years. The Abbasids established the caliphate in the new city of Baghdad, situated on the Tigris a short distance north of Ctesiphon and designed as a new city, free of the factions of the old Umayyad garrison cities of Al-Kufah, Wasit, and Al-Basrah. The strength of the Abbasid dynasty would be its Turkish troops. |

Despite the development of a distinctive Islamic culture, the military problems of the empire were left unsolved. The Abbasids were under pressure from the infidel on several fronts—Turks in Central Asia, pagans in India and the Hindu Kush, and Christians in Byzantium. War for the faith or jihad, against these infidels was a Muslim duty. But, whereas the Umayyads had been expansionists and had seen themselves as heads of a military empire, the Abbasids were more pacific and saw themselves as the supporters of more than an Arab conquering militia. Yet rebellions within the imperial frontiers had to be contained and the frontiers protected.

Rebellion within the Arab empire took the form of peasant revolts in Azerbaijan and Khorasan, coalesced by popular religious appeals centered on men who assumed or were accorded mysterious powers. Abu Muslim — executed in 755 by the second 'Abbasid caliph, al-Mansur, who feared his influence — became one such messianic figure. Another was al-Muqanna' (Arabic: “the Veiled One”), who used Abu Muslim's mystique and whose movement lasted from 777 to 780. The Khorram-dinan (Persian: “Glad Religionists”), under the Azerbaijanian Babak (816–838), also necessitated vigorous military suppression. Babak eluded capture for two decades, defying the caliph in Azerbaijan and western Persia, before being caught and brought to Baghdad to be tortured and executed. These heresiarchs revived such creeds as that of the anti-Sassanid religious leader Mazdak (died 528 or 529), expressive of social and millenarian aspirations that were later canalized into Sufism on the one hand and into Shi'ism on the other.The beginning of European JudaismThe Arabs continued their wars with Rome, these wars also had a religious overtone. One group caught in the middle were the "Khazars". These were members of a confederation of Turkic-speaking tribes that had, in the late 6th century A.D, established a major commercial Empire covering the Caucasus region of Russia. The Khazars and Arabs fought each other in Armenia and other places. There was apparently pressure on the Khazars from their allies the Romans, to convert to Christianity, while at the same time, there was also pressure put on them by the Arabs to accept Islam. The Khazars did neither, instead they chose the Hebrew religion, which they knew to be a choice that both sides would have to respect, since both of their religions were based on the Hebrew religion. The prominence and influence of the Khazar state was reflected in its close relations with the Byzantine Emperors: Justinian II (704) and Constantine V (732) each had a Khazar wife. Itil the Khazar capital in the Volga delta was a great commercial center. The Khazar Empire fell when Sviatoslav, duke of Kiev Russia (945–72), and son of Igor and of St. Olga; defeated its army in 965 A.D. The Khazars are the progenitors of European Jewry, the entomology of the term Jew or Jewish probably relates to these people. |

The Saffarids

Over-exploitation of agriculture by Arab governors had debilitated rural life, and Kharijites (puritanical Arabs), who found refuge in Sistan (Persia's southeastern border area) from the Umayyads, organized or attracted bands of local peasants and vagabonds who had strayed south from Khorasan. Kharijite bands isolated the cities and threatened their supplies. Sistan needed an urban champion who could come to terms with the Kharijites and divert them to what could legitimately be termed jihad across the border, thereby forming the gangsters into a well-disciplined loyal army. Such a man was Ya'qub ibn Layth, who founded the Saffarid dynasty, the first purely Persian dynasty of the Islamic era, and which threatened the Muslim empire with the first resurgence of Persian independence.

Ya'qub ibn Layth seized Baghdad's breadbaskets—Fars and Khuzestan—and drove the Tahirid emir from Neyshabur. His march on Baghdad itself was halted only by the stratagem devised by the Arab caliph's commander in chief: who inundated Ya'qub's army by bursting dikes. Ya'qub died soon after in 879. He had made an empire, minted his own coinage, fashioned a new style of army loyal to its leader rather than to any religious or doctrinal concept, and required that verses in his praise be put into his own language—Persian—from Arabic, which he did not understand. He began the Persian resurgence.

The collapse of the Tahirid viceroyalty left the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad faced with a power vacuum in Khorasan and southern Persia. The Arab caliph reluctantly confirmed Ya'qub's brother Amr as governor of Fars and Khorasan, but withdrew his recognition on three occasions, and Amr's authority was disclaimed to the Khorasanian pilgrims to Mecca when they passed through Baghdad. But Amr remained useful to Baghdad so long as Khorasan was victimized by the rebels Ahmad al-Khujistani and Rafi' ibn Harthama. After Rafi' had been finally defeated in 896, Amr's broader ambitions gave the caliph al-Mu'tadid his chance. Amr conceived designs on Transoxania, but there the Samanids held the caliph's license to rule, after having nominally been Tahirid deputies. When Amr demanded and obtained the former Tahirid tutelage over the Samanids in 898, the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad could leave the Saffarid and Samanid to fight each other, and the Samanid Isma'il (reigned 892–907) won. Amr was sent to Baghdad, where he was put to death in 902. His family survived as Samanid vassals in Sistan.

| The paintings below, supposedly from "The Book of Nativities" (Kitab al-Mawalid) was a five part astronomical work that was translated from Pahlavi into Arabic in 750. It was ascribed to Zoroaster and according to the Iranian historian Sa’id ibn-Khurasan-Khurreh, "it was translated by Mahankard, an Iranian scholar from among the books of Zoroaster". As with most of these things, it's probably not true. For one thing, many of the figures appear Mongol, the Mongols didn't reach Persia until 1220 A.D. The painting on the left is suppose to be Iblis, the Muslim Satan. But this Satan has an architects square, the Devil as a builder? It seems more likely that this Zodiac represents Persia's invaders, and the Persians (The Black figures) ever changing relationships with them. The fact that it shows "White" Arabs (a modern myth - those modern people are of course Turks), indicates that it is a modern forgery. |

|  |

The Samanids

The eponym of the Samanids' origin was Saman-Khoda, a landlord in the district of Balkh, and according to the dynasty's claims, a descendant of Bahram Chubin, the Sassanian general. Saman had became a Muslim and his four grandsons were rewarded for services to the Arab caliph al-Ma'mun (reigned 813–833) and received the caliph's investiture for areas that included Samarkand and Herat. They thus gained wealthy Transoxanian and the east Khorasanian entry-port cities, where they could profit from trade that reached across Asia, even as far as Scandinavia. And from providing Turkish slaves—much in demand in Baghdad as royal troops (Mamluks). The Samanids also protected the frontiers and provided security for merchants in Bukhara, Samarkand, Khujand, and Herat. With one transitory exception, they upheld Sunnism and at each new accession to power, paid a tribute to Baghdad for the tokens of investiture from the caliph whereby their rule represented lawful authority.

Thus, legal transactions in Samanid realms would be valid, and Baghdad received tribute in return for the insignia prayed over and signed by the Arab caliph. This tribute took the place of regular revenue, so that it represented a solution of the taxation problems and consequent resentments that had bedeviled the Umayyad regime. In modern assessments of imperial power, the Arab caliph in Baghdad may seem to have been politically the weaker for this type of arrangement, but ensuring the reign of Islam in peripheral provinces was important to the Arab caliphs. As was to insure Islam's portals to East Asia were adequately guarded, and the supply of Turkish slaves essential for the caliph's bodyguard was maintained, and that the Turkish pagan tribes were converted to Islam under the Samanids.

It was during the rule of Abbasid caliph Harun ar-Rashid, that the caliphs began assigning Egypt to Turks rather than to Arabs. The first Turkish dynasty in Egypt was that of Ibn Tulun who entered Egypt in 868. It is not known exactly what coalition of peoples the original Arab conquering armies employed (lowly populated Arabia could not have supplied sufficient troops), likely there was a large force of Greeks left over from the period of Greek occupation. But with the Arab troops taking to a sedentary lifestyle and banditry, the Arab caliphs had no choice but to seek troops from other sources.

The End of Black rule in Persia |

The Turks

History

Little is known about the origins of the Turkic peoples, and much of their history even up to the time of the Mongol conquests in the 10th–13th centuries is shrouded in obscurity. Chinese documents of the 6th century A.D. refer to the empire of the T'u-chüeh as consisting of two parts, the northern and western Turks. This empire submitted to the nominal suzerainty of the Chinese T'ang dynasty in the 7th century, but the northern Turks regained their independence in 682, and retained it until 744. The Orhon inscriptions, the oldest known Turkic records (8th century), refer to this empire and particularly to the confederation of Turkic tribes known as the Oguz; and the Uighur, who lived along the Selenga River (in present-day Mongolia); and to the Kyrgyz, who lived along the Yenisey River (in north-central Russia). When able to escape the domination of the T'ang dynasty, these northern Turkic groups fought each other for control of Mongolia from the 8th to the 11th century, when the Oguz migrated westward into Persia and Afghanistan.

In Persia the family of Oguz tribes known as Seljuqs created an empire that by the late 11th century stretched from the Amu Darya south to the Persian Gulf and from the Indus River west to the Mediterranean Sea. In 1071 the Seljuq sultan Alp-Arslan defeated the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert and thereby opened the way for several million Oguz tribesmen to settle in Anatolia. These Turks came to form the bulk of the population there, and one Oguz tribal chief, Osman, founded the Ottoman dynasty (early 14th century) that would subsequently extend Turkish power throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The Oguz are the primary ancestors of the Turks of present-day Turkey. The Uighur were driven out of Mongolia and settled in the 9th century in what is now the Xinjiang region of northwestern China. Some Uighur moved westward into what is now Uzbekistan, where they forsook nomadic pastoralism for a sedentary lifestyle. These people became known as Uzbek, named for a ruler of a local Mongol dynasty of that name.

| Note: The reason why Turks have Arab names, is because as they converted to Islam, they took on Arab names. Thus Alp-Arslan assumed the name of "Muhammad bin Da'ud Chaghri" when he embraced Islam. The Turks of Saudi Arabia will often take the name or nickname "Turki" in deference to their origins. |

The Ghaznavids (Islamic Dynasty of Turkish slave origin)

The Tajikistanian (Central Asian) poet Rudaki (858-941), in a poem about the Samanid emir's court, describes how “row upon row” of Turkish slave guards were part of its adornment. From these Turkic guard ranks two military families arose—the Simjurids and Ghaznavids—who ultimately proved disastrous to the Samanids. The Simjurids received an appendage in the Kuhestan region of southern Khorasan. Alp Tigin founded the Ghaznavids when he established himself at Ghazna (modern Ghazni, Afghanistan) in 962. He and fellow Turk, Abu al-Hasan Simjuri, as Samanid generals, competed with each other for the governorship of Khorasan and control of the Samanid Empire by placing on the throne emirs they could dominate. Abu al-Hasan Simjuri died in 961, but a court party instigated by men of the scribal class—civilian ministers as contrasted with Turkish generals—rejected Alp Tigin's candidate for the Samanid throne, Mansur I was installed, and Alp Tigin prudently retired to his fief of Ghazna. Thus the Simjurids enjoyed control of Khorasan south of the Oxus river only.

The struggles of the Turkish slave generals for mastery of the Samanid throne, with the help of shifting allegiance from the court's ministerial leaders, both demonstrated and accelerated the Samanid decline. Samanid weakness attracted into Transoxania the Qarluq Turks, who had recently converted to Islam. They occupied Bukhara in 992, and established in Transoxania the Qarakhanid or Ilek Khanid dynasty. Alp Tigin had been succeeded at Ghazna by Sebüktigin (died 997). Sebüktigin's son Mahmud made an agreement with the Qarakhanids whereby the Oxus river was recognized as their mutual boundary. Thus the Samanids' dominion was divided and Mahmud was freed to advance westward into Khorasan to meet the Buyids.

The Buyids

Buyids/Buyahids/or Buyyids, were a dynasty that originated from Daylaman in Gilan, Northern Persia. The founders of the Būyid confederation were ‘Alī ibn Būyah and his two younger brothers, al-Hassan and Ahmad. The Deylamites/Dailamites were a possibly Persian people, inhabiting the mountainous regions of northern Persia on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea. The earliest Zoroastrian and Christian sources indicate that the Dailamites originally came from Anatolia near the Tigris River. They spoke the Deilami language, a northwestern Persia dialect similar to that of the neighbouring Gilites.During the Sassanid period, they were employed as high-quality infantry. According to the Byzantine historians Procopius and Agathias, they were a warlike people and skilled in close combat, being armed each with a sword, a shield and spears or javelins. They supported the rebellion of the Parthian general Bahram Chobin against Persian King Khosrau II. Bahram Chobin sat on the Persian throne as Bahram VI for one year (590-591). But Khosrau II later employed an elite detachment of 4,000 Dailamites as part of his guard. The Sassanid general Wahriz, who was sent by Khosrau I in 570 to capture Yemen, was also probably of Dailamite descent, and his troops included Deilamites, who would later play a significant role in the conversion of Yemen to the nascent Islam. Following the Persian defeat at the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, the 4,000-strong Dailamite contingent of the Persian guard, along with other Persian units, defected to the Arab side, and converted to Islam. Nevertheless, the Dailamites managed to resist the Arab invasion of their own mountainous homeland for several centuries under their own local rulers.

At the end of the 9th century, the Buyids had been stirred into warlike activity by a number of factors, among them the rebel Rafi' ibn Harthama's attempt to penetrate their region, ostensibly with Samanid support - Samanid Amr ibn Layth had pursued the rebel into the region. Other factors had been the formation of Shi'ite principalities in the area, and continued Samanid attempts to subjugate them. After the Tahirid collapse, the lack of stability in northern Persia south of the Elburz Mountains attracted many Daylamite mercenaries into the area on military adventures. Among them Makan ibn Kaki who had served the Samanids with his compatriots, the sons of Buyeh, and their allies the Ziyarids, under Mardavij. It was Mardavij who introduced the three Buyid brothers to the Persian plateau, where he established an empire reaching as far south as Esfahan and Hamadan. Mardavij was murdered in 935, and his Ziyarid descendants sought Samanid protection.

Mardavij's expansionism south of the Elburz was then taken up by his Buyid lieutenants: the eldest brother Ali, consolidated power for himself in Esfahan and Fars, and obtained the Arab caliph's recognition. Another brother Hasan, occupied Rayy and Hamadan; and the youngest brother Ahmad, took Kerman in the southeast and Khuzestan in the southwest.

By now the Arab caliphs of the 960s period, al-Muttaqi and then al-Mustakfi, were at the mercy of their Turkish slaves in the palace guard. Their Turkish generals competed with each other for the office of amir al-umara' (commander in chief), who virtually ruled Iraq on behalf of the caliphs.

The other Turks

Although the Buyids were careful to avoid sectarian strife, family quarrels weakened them sufficiently for Mahmud of Ghazna to take Rayy in 1029. But Mahmud (reigned 998–1030) went no farther: his dynasty paid great deference to the Arab caliphate's legitimating power, and he made no bid to contest the Buyids' role as its protectors. Mahmud's agreement with the Samanids that the Oxus river should be their mutual boundary held, but south of the river, the Ghaznavids had to contend with their own distant relatives, the Oguz Turks. Contrary to the sage counsel of Persian ministers, Mahmud and his successor Mas'ud (reigned 1031–41) permitted these Turk tribesmen to use Khorasanian grazing grounds, which they entered from north of the Oxus. These nomadic Turks, united under descendants of an Oguz leader named Seljuq, between 1038 and 1040, drove the Ghaznavids out of northeastern Persia, the final encounter was at Dandanqan in 1040.

After their defeat by the Seljuq Turks, the Ghaznavid Turks, former patrons of Arab Islamic culture and letters, were deflected eastward into India, where Mahmud had already conducted successful raids. These raids took the form of jihad (or holy war), and the Ghaznavids carried Islam and Persian Muslim art to the Indian subcontinent. In Persia it was now the Seljuqs turn to create a new imperial synthesis with the Arab Abbasid caliphs.

Turkish Rule

The Seljuqs

Toghril Beg proclaimed himself sultan at Neyshabur in 1038, and had espoused strict Sunnism, by which he gained the Arab caliph's confidence and undermined the Buyid position in Baghdad. The Oguz Turks had accepted Islam late in the 10th century, and their leaders displayed a convert's zeal in their efforts to restore a Muslim polity along orthodox lines. Their efforts were made all the more urgent by the spread of Fatimid Isma'ili propaganda (Arabic da'wah) in the eastern Caliphate by means of an underground network of propagandists or da'is, intent on undermining the Buyid regime, and also by the threat posed by the Christian Crusaders.

The Buyids' usurpation of the Arab caliph's secular power, had given rise to a new theory of state formulated by al-Mawardi (died 1058). Al-Mawardi's treatise partly prepared the theoretical ground for Toghril Begs attempt to establish an orthodox Muslim state in which conflict between the Arab caliph-imam's spiritual-juridical authority on the one side, and the secular power of the sultan on the other, could be resolved, or at least regulated, by convention. Al-Mawardi reminded the Muslim world of the necessity of the imamate; but the treatise realistically admitted the existence of, and thus accommodated the fact of military usurpation of power. The Seljuq Turks own political theorist al-Ghazali (died 1111) carried this admission further, by explaining that the position of a powerless Arab caliph, overshadowed by a strong Seljuq Turk master, was one in which the latter's presence guaranteed the former's capacity to defend and extend Islam.

The Arab caliph al-Qa'im (reigned 1031–75) replaced the last Buyid's name, al-Malik al-Rahim, in the khutbah and on the coins, with that of Toghril Beg; and after protracted negotiation ensuring restoration of the caliph's dignity after Shi'ite subjugation, Toghril entered Baghdad in December 1055. The Arab caliph enthroned him and married a Seljuq princess (see below). Buyid power was thus terminated, ending what Vladimir Minorsky, the great Persiaologist, called the “Persian intermezzo.”

The Arabs, like the Berbers, were very fond of White Women, especially Turkish White Women. Their harems were always well stocked with them. Even the Bedouin Nomads in the desert, had Turkish Wives!

|

|

|

|

After Toghril had campaigned successfully as far as Syria, he was given the title of “king of the east and west.” The new situation was justified by the theory that existing practice was legal whereby a new caliph could be instituted by the sultan, who possessed effective power and sovereignty, but that thereafter the sultan owed the caliph allegiance because only so long as the caliph-imam's juridical faculties were recognized could government be valid.

Toghril Beg died in 1063. His heir, Alp-Arslan, was succeeded by Malik-Shah in 1072, and the latter's death in 1092 led to succession disputes out of which Berk-Yaruq emerged triumphant to reign until 1105. After a brief reign, Malik-Shah II was succeeded by Muhammad I (reigned 1105–18). The last “Great Seljuq” was Sanjar (1118–57), who had earlier been governor of Khorasan.

The Khwarezm-Shah

With the fall of the Seljugs, the Turk Anush Tigin Gharchai, a former slave of the Seljuq sultans, and who was appointed the governor of Khwarezm, established the Khwarezm-Shah dynasty (1077–1231). His son Qutb ud-Dīn Muhammad I by 1205 had conquered the remaining parts of the Great Seljuq Empire, proclaiming himself Shah (king). He eventually became known as the Khwarezmshah. In 1212 he defeated the Gur-Khan Kutluk and conquered the lands of the Kara Khitay, now ruling a territory from the Syr Darya almost all the way to Baghdad, and from the Indus River to the Caspian Sea.Genghis Khan

In 1218, Genghis Khan sent a trade mission to the Khwarezm-Shah, but at the town of Otrara (a Central Asian town that was located along the Silk Road near the current town of Karatau in Kazakhstan) the governor there, suspecting the Khan's ambassadors to be spies, confiscated their goods and executed them. Genghis Khan demanded reparations, which the Shah refused to pay. Genghis Khan then sent a second, purely diplomatic mission, they too were murdered. Genghis retaliated with a force of 200,000 men, launching a multi-pronged invasion, his guides were Muslim merchants from Transoxania. During the years 1220–21, Bukhara, Samarkand, Herat (all Central Asian cities), Tus (Susa), and Neyshabur (Persian cities) were razed, and the whole populations were slaughtered. (This represented the first wholesale slaughter of Black Persians).

|

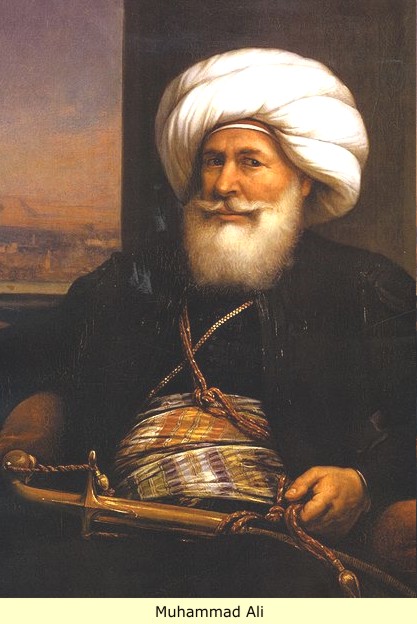

Arabs lose, and Turks take, Rule over Islam

A second Mongol invasion began when Genghis Khan's grandson Hülegü Khan crossed the Oxus river in 1256 and destroyed the Assassin fortress at Alamut. With the disintegration of the Seljuq empire, the Arab Caliphate had reasserted control in the area around Baghdad and in southwestern Persia. In 1258 Hülegü besieged Baghdad, Al-Musta'sim, the last Arab Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, was trampled to death by mounted troops (in the style of Mongol royal executions). The Abbasids rule resumed in Mamluk governed Egypt in 1261, from where they continued to claim authority in religious matters only. That is until 1519, when all power was formally transferred to the Ottomans in their capital of Constantinople.| Turkish subjugation of the Arabs became complete, when Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II (1808-39), instructed the Albanian Turk ruler of Egypt, the viceroy "Muhammad Ali" to put down a rebellion by Wahhabis Arabs in the Hejaz. Muhammad Ali sent an Albanian army to Arabia, that between 1811 and 1813, expelled the Wahhabis Arabs from the Hejaz. In a further campaign (1816-18), Ibrahim Pasha, the viceroy's eldest son, defeated the Wahhabis in their homeland of Najd, and brought central Arabia also under Albanian control. As in the rest of the Middle East, the Ottoman Turks retained military and political control over Arabia until the end of WW I, after which time, it was passed to local Turks. |

|  |

Hülegü hoped to consolidate Mongol rule over western Asia and to extend the Mongol empire as far as the Mediterranean, an empire that would span the Earth from China to the Levant. Hülegü made Persia his base, but the Mamluks of Egypt (former Turkish slave soldiers of the Arab caliphate, who rebelled in 1250 and established their own dynasty in Egypt.) prevented him and his successors from achieving their great imperial goal, by decisively defeating a Mongol army at Ayn Jalut in 1260. Instead, a Mongol dynasty called the Il-Khans, or “deputy khans” to the great khan in China, was established in Persia to attempt repair of the damage done by the first Mongol invasion. (It is at this time, at the battle of Ayn Jalut, that Black Egyptians demonstrate that almost two thousand years of occupation, had not diminished their genius. At this battle, they unveil the worlds first "Gun" and the Mamluks use it successfully to repel the Mongols).

More paintings from The Book of Nativities |

|  |

Timur (Tamurlaine "Timur the Lame")

Timur, who claimed descent from Genghis Khan's family, was a member of the Turkicized Barlas tribe, a Mongol subgroup that had settled in Transoxania (now roughly corresponding to Uzbekistan). After taking part in Genghis Khan's son Chagatai's campaigns in that region, and after the death in 1357 of Transoxania's ruler, Amir Kazgan. Timur declared his fealty to the khan of nearby Kashgar: Tughluq Temür, who had overrun Transoxania's chief city Samarqand, a city in east-central Uzbekistan in 1361. In about 1370 Timur turned against Amir Husayn, besieged him in Balkh, and after Husayn's assassination, proclaimed himself at Samarqand, sovereign of the Chagatai line of khans and restorer of the Mongol empire. |

In 1383 Timur began his conquests in Persia with the capture of Herat. The Persian political and economic situation was extremely precarious. The signs of recovery visible under the later Mongol rulers known as the Il-Khanid dynasty, had been followed by a setback after the death of the last Il-Khanid, Abu Said in 1335. The vacuum of power was filled by rival dynasties, torn by internal dissensions and unable to put up joint or effective resistance. Khorasan and all eastern Persia fell to him in 1383–85; Fars, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Georgia all fell between 1386 and 1394. In the intervals, he was engaged with Tokhtamysh, then khan of the Golden Horde, whose forces invaded Azerbaijan in 1385 and Transoxania in 1388, defeating Timur's generals. In 1391 Timur pursued Tokhtamysh into the Russian steppes and defeated and dethroned him; but Tokhtamysh raised a new army and invaded the Caucasus in 1395. After his final defeat on the Kur River, Tokhtamysh gave up the struggle; Timur occupied Moscow for a year.

The Slaughter and Annialation of Black Persians

Meanwhile, the revolts that broke out all over Persia while Timur was away on these campaigns were repressed with ruthless vigour; whole cities were destroyed, their populations massacred, and towers built of their skulls.In 1398 Timur invaded India on the pretext that the Muslim sultans of Delhi were showing excessive tolerance to their Hindu subjects. He crossed the Indus River on September 24 and, leaving a trail of carnage, marched on Delhi. The army of the Delhi sultan Mahmud Tughluq was destroyed at Panipat on December 17, and Delhi was reduced to a mass of ruins, from which it took more than a century to emerge. By April 1399 Timur was back in his own capital. An immense quantity of spoil was carried away; according to Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, 90 captured elephants were employed to carry stones from quarries to erect a mosque at Samarqand.

After the decline of the Timurid Empire (1370–1506), Persia was politically splintered, giving rise to a number of religious movements. The demise of Tamerlane’s political authority created a space in which several religious communities, particularly Shi’i ones, could now come to the fore and gain prominence. Among these were a number of Sufi brotherhoods, the Hurufis, Nuqtawis and Musha‘sha‘. Of these various movements, the Safawid Qizilbash was the most politically resilient.

The Safavids

Sheikh Haydar, was a Turkish speaker of mixed ancestry from the Gilan Province: the Safavids were of ethnic Georgian, Azerbaijani, Kurdish, and Greek ancestry, he led a movement that had begun as a Sufi order under his ancestor, Sheikh Safi al-Din of Ardabil (1253–1334). This order may be considered to have originally represented a puritanical, but not legalistically so, reaction against the sullying of Islam, and the staining of Muslim lands by the Mongol infidels. By the 15th century, the Safavid movement could draw on both the mystical emotional force of Sufism and the Shi'ite appeal to the oppressed populace to gain a large number of dedicated adherents. Sheikh Haydar inured his numerous followers to warfare by leading them on expeditions from Ardabil against Christian enclaves in the nearby Caucasus. He was killed on one of these campaigns. His son Isma'il was to avenge his death and lead his army to a conquest of Persia.The new Persian empire lacked the resources that had been available to the caliphs of Baghdad in former times through their dominion over Central Asia and the West. Asia Minor and Transoxania were gone, and the rise of maritime trade in the West was detrimental to a country whose wealth had depended greatly on its position on important east-west overland trade routes. The rise of the Ottomans impeded Persian westward advances, and contested the Safavids' control over both the Caucasus and Mesopotamia. Years of warfare with the Ottomans imposed a heavy drain on the Safavids' resources. The Ottomans threatened Azerbaijan itself, finally in 1639 the Treaty of Qasr-e Shirin (also called the Treaty of Zuhab) gave Yerevan in the southern Caucasus to Persia and Baghdad and all of Mesopotamia to the Ottomans.

Safavid Husayn I (reigned 1694–1722) was of a pious temperament and was especially influenced by the Shi'ite divines, whose conflicting advice, added to his own procrastination. This sealed the sudden and unexpected fate of the Safavid empire. One Mahmud, a former Safavid vassal in Afghanistan, captured Esfahan and murdered Husayn in his cell in the beautiful madrasah (religious school) built in his mother's name.

In 1723 the Ottomans, partly to secure more territory and partly to forestall Russian aspirations in the Caucasus, took advantage of the disintegration of the Safavid realm and invaded from the west, ravaging western Persia. Nadr, an Afsharid Turkmen from northern Khorasan, was eventually able to reunite Persia, a process he began on behalf of the Safavid prince Tahmasp II (reigned 1722–32), who had escaped. After Nadr had cleared the country of Afghans, Tahmasp II made him governor of a large area of eastern Persia.

Nadr later dethroned Tahmasp II in favour of the latter's son, the more pliant 'Abbas III. His successful military exploits, however, which included victories over rebels in the Caucasus, made it feasible for this stern warrior himself to be proclaimed monarch—as Nadir Shah—in 1736. He attempted to mollify Persian-Ottoman hostility by establishing in Persia a less aggressive form of Shi'ism, which would be less offensive to Ottoman sensibilities, but this experiment did not take root. Nadir Shah's need for money drove him to embark on his celebrated Indian campaign in 1738–39. His capture of Delhi and of the Mughal emperor's treasure gave Nadir booty in such quantities that he was able to exempt Persia from taxes for three years. His Indian expedition temporarily solved the problem of how to make his empire financially viable.

But on Nadir Shah's death his great military machine dispersed, its commanders were bent on establishing their own states. Ahmad Shah Durrani founded a kingdom in Afghanistan based in Kandahar. Shah Rokh, Nadir Shah's blind grandson, succeeded in maintaining himself at the head of an Afsharid state in Khorasan, its capital at Mashhad. The Qajar chief Muhammad Hasan took Mazanderan south of the Caspian Sea. Azad Khan, an Afghan, held Azerbaijan, whence Mohammad Hasan Khan Qajar ultimately expelled him. The Qajar chief, therefore, disposed of this post-Nadir Shah Afghan remnant in northwestern Persia but was himself unable to make headway against a new power arising in central and southern Persia, that of the Zands.

The Zand dynasty (Parthians) 1750–79

Muhammad Karim Khan Zand entered into an alliance with the Bakhtyari chief 'Ali Mardan Khan in an effort to seize Esfahan—then the political centre of Persia—from Shah Rokh's vassal, Abu al-Fath Bakhtyari. Once this goal was achieved, Karim Khan and 'Ali Mardan agreed that Shah Sultan Husayn Safavi's grandson, a boy named Abu Turab, should be proclaimed Shah Isma'il III in order to cement popular support for their joint rule. The two also agreed that the popular Abu al-Fath would retain his position as governor of Esfahan, 'Ali Mardan Khan would act as regent over the young puppet, and Karim Khan would take to the field in order to regain lost Safavid territory. 'Ali Mardan Khan, however, broke the compact and was killed by Karim Khan, who gained supremacy over central and southern Persia and reigned as regent or deputy (vakil) on behalf of the powerless Safavid prince, never arrogating to himself the title of shah. Karim Khan made Shiraz his capital and did not contend with Shah Rokh (reigned 1748–95) for the hegemony of Khorasan. He concentrated on Fars and the centre but managed to contain the Qajar in Mazanderan, north of the Elburz Mountains. He kept Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar a hostage at his court in Shiraz, after repulsing Muhammad Hasan Qajar's bids for extended dominion.

Karim Khan's geniality and common sense inaugurated a period of peace and popular contentment, and he strove for commercial prosperity in Shiraz, a centre accessible to the Persian Gulf ports and trade with India. After Karim Khan's death in 1779, Agha Muhammad Khan escaped to the Qajar tribal country in the north, gathered a large force, and embarked on a war of conquest.

The Qajar dynasty (1796–1925)

Between 1779 and 1789 the Zands fought among themselves over their legacy. In the end it fell to the gallant Lotf 'Ali, the Zands' last hope. Agha Muhammad Khan relentlessly hunted him down until he overcame and killed him at the southeastern city of Kerman in 1794. In 1796 Agha Muhammad Khan assumed the imperial diadem, and later in the same year he took Mashhad. Shah Rokh died of the tortures inflicted on him to make him reveal the complete tally of the Afsharids' treasure. Agha Muhammad was cruel and he was avaricious.

Karim Khan's commercial efforts were nullified by his successors' quarrels. With cruel irony, attempts to revive the Persian Gulf trade were followed by a British mission from India in 1800, which ultimately opened the way for a drain of Persian bullion to India. This drain was made inevitable by the damage done to Persia's productive capacity during Agha Muhammad Khan's campaigns to conquer the country.

The age of imperialism

Fath 'Ali Shah (reigned 1797–1834), in need of revenue after decades of devastating warfare, relied on British subsidies to cover his government's expenditures. Following a series of wars, he lost the Caucasus to Russia by the treaties of Golestan in 1813 and Turkmanchay (Torkman Chay) in 1828, the latter of which granted Russian commercial and consular agents access to Persia. This began a diplomatic rivalry between Russia and Britain—with Persia the ultimate victim—that resulted in the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention giving each side exclusive spheres of influence in Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet.

The growth of European influence in Persia and the establishment of new transportation systems between Europe and the Middle East were followed by an unprecedented increase in trade that ultimately changed the way of life in both urban and rural areas of Persia. As with other semicolonized countries of this era, Persia became a source of cheap raw materials and a market for industrial goods from Western countries. A sharp drop in the export of manufactured commodities was accompanied by a significant rise in the export of raw materials such as opium, rice, tobacco, and nuts. This rapid change made the country more vulnerable to global market fluctuations and, because of an increase in acreage devoted to nonfood export crops, periodic famine. Simultaneously, in an effort to increase revenue, Qajar leaders sold large tracts of state-owned lands to private owners—most of whom were large merchants—subsequently disrupting traditional forms of land tenure and production and adversely affecting the economy.

Hajji Mirza Aghasi, a minister of Mohammad Shah (reigned 1834–48), tried to activate the government to revive sources of production and to cement ties with lesser European powers, such as Spain and Belgium, as an alternative to Anglo-Russian dominance, but little was achieved. Naser al-Din Shah (reigned 1848–96) made Persia's last effort to regain Herat, but British intervention in 1856–57 thwarted his efforts. Popular and religious antagonism to the Qajar regime increased as Naser al-Din strove to raise funds by granting foreign companies and individuals exclusive concessions over Persian import and export commodities and natural resources in exchange for lump cash payments. The money paid for concessions was ostensibly for developing Persia's resources but instead was squandered by the court and on the shah's lavish trips to Europe.

Popular protest and the Constitutional Revolution